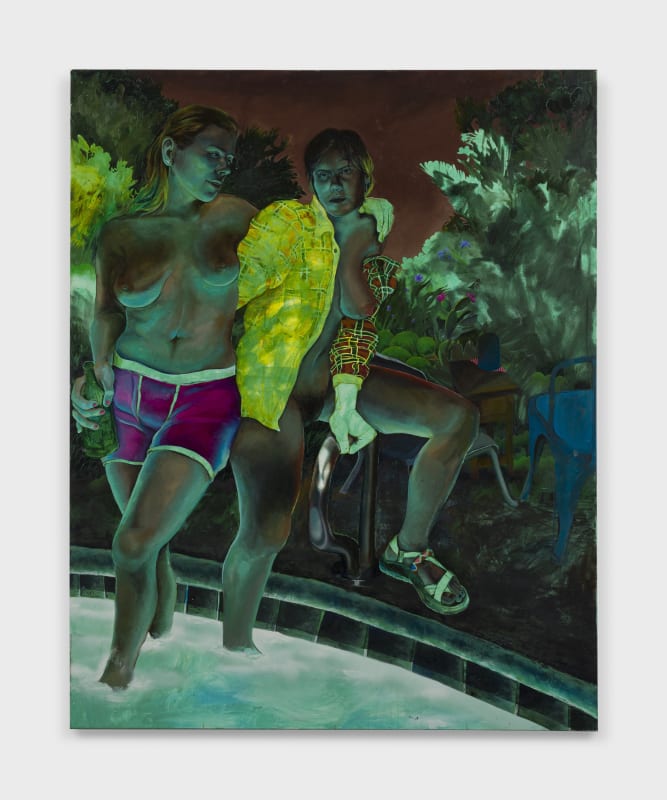

The descent towards the end of the world has rarely looked more beguiling than in Natalie Strait’s Monsoon Season. Lit by the eerie glow of a swimming pool at night or the otherworldly light of a full moon, her latest exhibition features a series of eight portraits depicting women luxuriating in these picturesque yet ever-so-slightly nightmarish environments. She tells us, “Monsoon Season is a show of semi-autobiographical paintings exploring being a young woman alive in western America when everything feels like it’s on a slow but neverending downward spiral and all you can do is just keep hanging out.”

Inspiration for the figures occupying Strait’s debut solo show (at Charles Moffett in New York), was drawn from vintage pornography discovered on Reddit and spreads from 1970s Playboys alongside the “unrelenting scroll of candid pictures of friends and selfies” on her phone. In a conversation over email, the Arizona-born artist explains: “I’m drawn to images that I find beautiful. Within that beauty though, I look for other factors at play – absurdity, humour, sexiness, power. Playboy has a lot of that. I don’t copy the images necessarily; the figures’ faces and many other parts of the painting are derived from my imagination or other random references, but that starting point informs the energy of the painting.”

In typical style, Strait infuses personal and popular culture references with both real and imagined details, recasting the figures in new locations, and introducing elements which strike the “precarious balance of the banal and fantastical” that characterises her work… a bright red nail polish, a soda can, the orange corner of a Cheetos bag.

Inspiration for the figures occupying Strait’s debut solo show (at Charles Moffett in New York), was drawn from vintage pornography discovered on Reddit and spreads from 1970s Playboys alongside the “unrelenting scroll of candid pictures of friends and selfies” on her phone. In a conversation over email, the Arizona-born artist explains: “I’m drawn to images that I find beautiful. Within that beauty though, I look for other factors at play – absurdity, humour, sexiness, power. Playboy has a lot of that. I don’t copy the images necessarily; the figures’ faces and many other parts of the painting are derived from my imagination or other random references, but that starting point informs the energy of the painting.”

In typical style, Strait infuses personal and popular culture references with both real and imagined details, recasting the figures in new locations, and introducing elements which strike the “precarious balance of the banal and fantastical” that characterises her work… a bright red nail polish, a soda can, the orange corner of a Cheetos bag.